3 Minute read

Associate Professor John FitzGerald from the Faculty of Arts is an expert in drug and alcohol policy whose research focuses on the cultural significance and lived experience of substance use. Here, he talks about using University expertise to help government and industry solve big-picture problems.

My research journey started because I wanted to understand the human experience of drugs beyond the neuro-chemical effects on the body. I have two PhDs, one in pharmacology, looking at the effects of the drug ecstasy, or MDMA. But humans are a lot more than just our neurochemistry, so I did a second PhD in cultural studies, focusing on the language and discourse that people use to articulate and understand the experience of psychoactive drugs. I’m a bit of a hybrid where I can speak across different research discourses of drug use – in the humanities but also in science.

There is no silver bullet when it comes to drug policy. In the 1980s, it was ‘just say No’. In the 90s and 2000s, there was a belief that there was a particular medication that could fix addiction. Now, we know there isn’t one solution to a big social problem. We know now that we can’t wage a war against drugs.

One of the projects I’m most proud of is my work with Victoria Police. In 2017, Victoria Police asked me to provide academic oversight of their drug policing, and to assist them in designing a new illicit drug strategy. I spent most of the year at Victoria Police helping them review their performance.

The end point is the new Victoria Police Drug Strategy 2020-2025, which focuses on targeted strategies to prevent community harm. It’s a remarkable advance from where they were. They saw the benefit of working with someone who could be objective and give them line of sight beyond their own patch. Recently, I worked with Victorian public health services and other university partners to develop RAPID, an early warning system for illicit drug use. The interdisciplinary team – which included myself and James Ziogas, Professor of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Gavin Reid, Professor of Bioanalytical Chemistry and Professor of Biochemistry, and Peter Scales, Professor of Chemical Engineering – were working with event providers and doing drug monitoring at music festivals as part of a University commercialisation pathway. In March 2020, when the pandemic started to have an effect on border controls and the drug market, we noticed the absence of a drug usually manufactured in China, which wasn’t a coincidence. Border controls would have an impact on our local drug consumers: when there’s drug scarcity, it can have a catastrophic effect at the local level. People will combine other drugs, and it can create more overdoses and other harms.

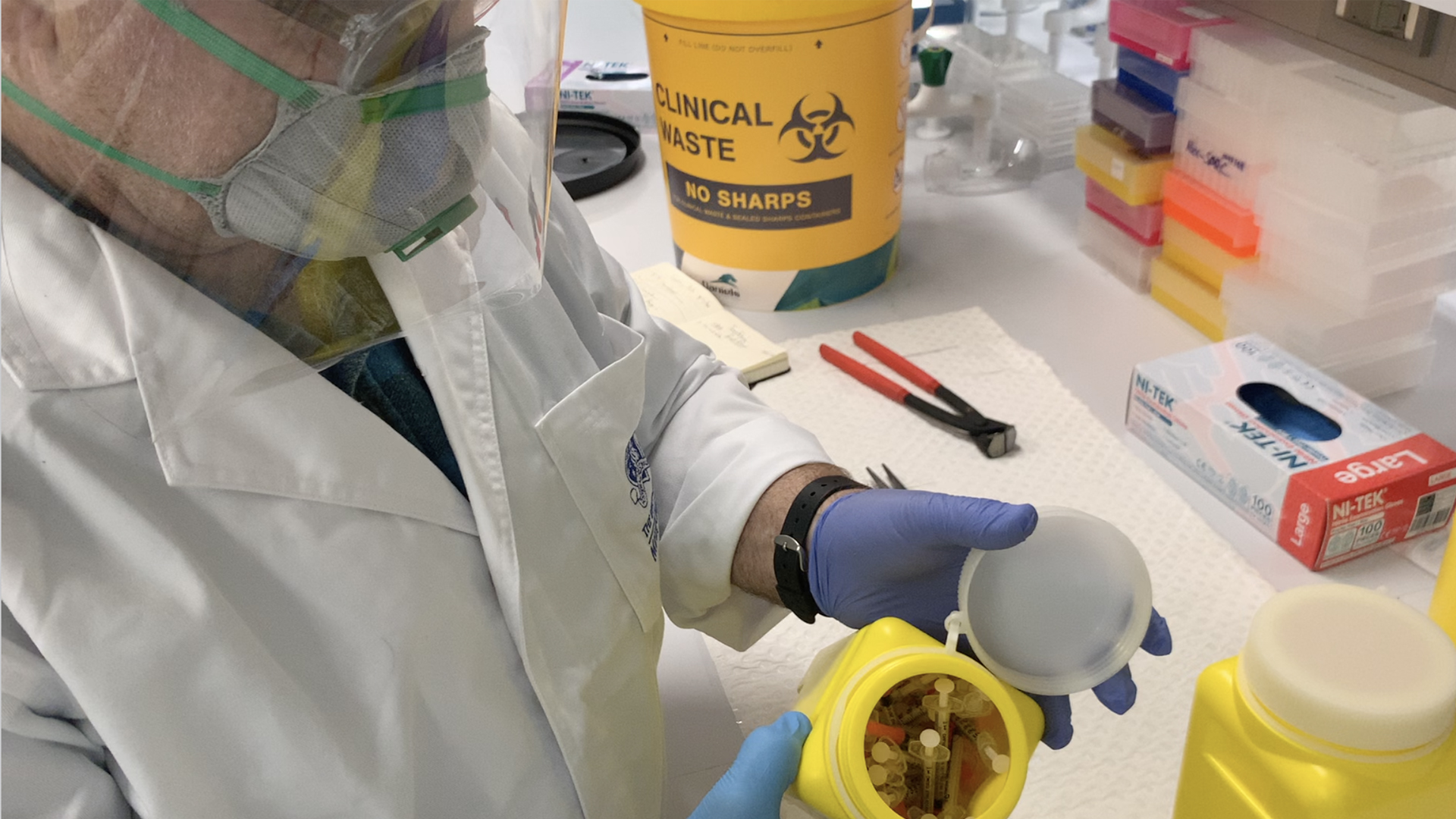

We approached the Victorian Health Department, which recognised the policy opportunity to test a new approach to drug monitoring at a time when the drug supply could well be in turmoil, with potentially serious implications for public health and community safety. By August, we were working with Dr Shaun Greene, of the Victorian Poisons Information Centre, to monitor overdose presentations at Victorian hospital emergency departments. We developed a new way of monitoring drug residues in used syringes, which had never been done in Australia before. We were also doing high-resolution wastewater testing by piggy-backing COVID-19 wastewater monitoring. And we were monitoring at a local level on a weekly basis. All this was going on while Victoria was in lockdown.

We provided weekly reports to the Health Department, which hadn’t been done before. We found that dealers introduced a new drug – a synthetic opioid – as a replacement for heroin. We were incredibly lucky that this new drug was not causing extra overdoses. It was a dress rehearsal for what could happen.

It required an extraordinary amount of collaboration and co-operation across all our key partners in frontline health services. They included the medically supervised injecting room at North Richmond Community Health, CoHealth in Braybrook, Youth Projects, Harm Reduction Victoria, and the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine. We worked with water utility providers and four different faculties at the University. I couldn’t have wished for a more cohesive partnership.

This is the only place in Australia where this has been done. We’re hopeful that the RAPID early warning system will become a mainstream feature of the health system fairly quickly. It’s gone through a full innovation cycle in 12 months.

As researchers, we can’t do what we do without our partners. I spent three years outside the University working at the statutory body Vic Health, first as part of their executive team and then as the CEO. Part of our job was to identify research that made a difference, and to find researchers who worked well with practitioners.

That was instrumental for me in learning how much we need to put our knowledge to work. The best way to do that is to develop questions with partners, based on what information they need and what’s important to them. We need to have those discussions early. This is the point of why we are here: to ask better questions. That’s how we get better outcomes.

People ask me what journal article has had the most impact. I show them the Victoria Police Drug Strategy 2020 to 2025, which is changing the way Victoria Police works. That’s a big, real-world impact for the University.

My long-term research focus is on early-warning systems – whether that’s in drug use or beyond. Right now, governments around the world are realising that early warning systems are incredibly important, whether they are about population change, climate change or illegal drugs. These are the systems that will indicate where we need innovation. Our research showed that monitoring the drug market on a weekly level produced incredible results.

This research is essential for government and industry because it gives them the ability to pre-empt problems. As a university, we have all the tools they need: it’s just about bringing people together. With the RAPID project, we were able to bring people together really effectively to understand the market in three or four months and produce results. I think it’s a really good model for what we can do across a number of different areas.

This project showed that when a university comes in, it enables industry and government to respond to these larger systemic changes in times of crisis, like COVID. When government and industry are in the trenches, we are here to help them see a wider picture.

As told to Kate Stanton

The University of Melbourne has announced the establishment of two new major investment funds dedicated to supporting Melbourne’s world-leading researchers to turn their extraordinary discoveries and innovation into commercial reality. Find out more about the University of Melbourne Genesis Pre-Seed Fund and Tin Alley Ventures.

First published on 17 February 2023.

Share this article

Related items

-

Catalyst: Alzheimer’s – Can we prevent it?

In ABC’s science program, Professor Cassandra Szoeke explains how lifestyle choices today may affect our chances of cognitive decline in the future.

-

Pursuit: How good cholesterol can keep women’s brains healthy

A healthy lifestyle keeps not only our bodies healthy, but our brains too. Research shows how this impacts on the very structure of a woman’s brain.

-

Pursuit: Can sunshine help your brain?

A landmark study shows regular physical activity is the number one protector against cognitive decline.