5 Minute read

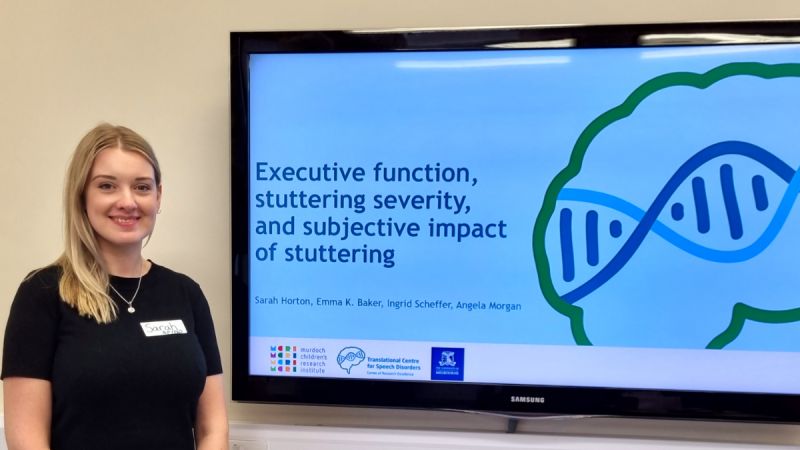

Life as a graduate researcher: Sarah Horton

Her PhD research has connected Sarah Horton to other people who stutter. She finds meaning and community through research that aims to answer some of the many questions medicine still has about stuttering.

Sarah Horton’s research is part of an international study seeking genes linked to stuttering. She is completing a PhD in Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences.

“I really enjoy the clinical focus of working as a speech pathologist because you get to know somebody one-on-one. You get to see their own individual journey and you're often working with their families as well,” Sarah says.

“But I also really like that with research, you might be contributing to something a lot bigger and helping lots and lots of people on their journeys.”

Sarah completed her undergraduate degree in arts and psychology at the University of Melbourne. The Melbourne curriculum helped her find an interest in science.

“I didn't do any science subjects in high school. But then my first breadth subject at the University of Melbourne was in optometry, which was a bit of a crash course in anatomy, biology and even physics,” she says.

Though it was all very new to Sarah, she found she liked science. And during her Master of Speech Pathology, she discovered a love for research.

“I thought it was something I'd probably come back to later in my career,” says Sarah.

But when Professor Angela Morgan offered her a PhD project linked to the genetics of stuttering study, Sarah took it.

Learn more about our graduate research options

Connecting with people who stutter through research

Stuttering can be isolating. And that isn’t always connected to the severity of stuttering.

I think a source of the isolation can be that identity of being a person who stutters, about potentially being found out or the anxiety of how people are going to react to it. Sarah Horton

Younger people who stutter are often ridiculed or bullied. As a result, people who stutter learn to hide it as much as they can.

In a way, Sarah was surprised to find herself researching stuttering – because she stutters herself.

Yet she has loved connecting with other people who stutter, first through the Stuttering Association for the Young (SAY) Australia and now her research.

“I've met hundreds of people who stutter now through this research, and I've asked every person, ‘What's stuttering been like for you?’,” she says.

“And as soon as I started meeting all these people and talking to them about their own experiences, I just thought that this is exactly where I want to be.”

How a PhD project may help explain why people stutter

“When somebody starts stuttering early in life, we don't know whether they'll be one of those people who will just stutter for a really brief period of time and then stop,” Sarah says.

Better understanding the biology of stuttering will help the genetics of stuttering research team understand what causes stuttering. It will help them better predict what outcomes people will have. And it will help better match people to therapies.

“Some kids will respond really well to the types of stuttering therapies we have at the moment. Some won't,” Sarah says.

Sarah’s PhD supervisors are Professor Angela Morgan and Professor Ingrid Scheffer. But she works with people from across the University of Melbourne, the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI) and the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research.

When the team runs into a problem, they can turn to experts across the Melbourne Biomedical Precinct for help.

What a PhD in health sciences may look like

Sarah spends most of her days at her desk at the MCRI. But she also has a place at the Audiology and Speech Pathology department at the University of Melbourne.

“It's been really helpful to access the statistical support through the librarians, and help with doing literature searches and systematic reviews,” she says.

Earlier on in her PhD, Sarah spent her time conducting speech assessments, collecting medical histories and interviewing people about their lived experiences with stuttering. The School of Health Sciences Graduate Researcher Allowance helped her purchase test forms needed for assessing participants.

Now she spends more time on data analysis and writing.

What I really enjoy is the fact that each day is quite different, but I also get to do a lot of training and learning as well. Sarah Horton

The graduate research services offers workshops and resources on topics from thesis writing to presentation skills that Sarah has attended. But the rarer opportunities like attending international conferences have been the real highlight of Sarah’s experience.

“It's a bit scary presenting and contributing. But it's very exciting to be in that space and to meet a lot of other people who have that niche interest that you do, and who are also just as passionate about it,” Sarah says.

“Also just getting to travel overseas is fun.”

After her PhD, Sarah will be looking for a way to balance her interest in teaching, research and clinical work. Yet she may not have to go very far at all for her next job opportunity.

“What's been really amazing about doing this project – but also a bit overwhelming – is that I have so, so much data and there are so many things I want to do with it,” Sarah says.

“I think I could make a really good case for a postdoctoral fellowship.”

Learn more about a PhD in Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences

First published on 16 May 2024.

Share this article

Keep reading

-

Why research with us

Explore the benefits of undertaking your graduate research at the University of Melbourne.

-

Your research options

Explore your options as a graduate researcher at the University of Melbourne.

-

Your study experience

Discover what it's like to be a graduate researcher. Find out about University life, support services, and opportunities for skills development.

-

How to apply

Find out how to apply for graduate research at the University of Melbourne.